CITATION

Prieto Torre M, Tejero Jurado R, Rodríguez Perálvarez ML. Therapeutic options in acute alcoholic hepatitis: Should we think about liver transplantation?. RAPD 2024;47(1):9-20. DOI: 10.37352/2024471.1

Introduction

Alcohol has been part of human culture for centuries and is currently the most widely consumed psychoactive substance in the world. Despite evidence of a progressive decline in its intake, more than 2.3 billion people (43% of the world's population) currently consume alcohol[1],[2]. Paradoxically, the amount of alcohol consumed per capita has risen from 5.5 litres in 2005 to 6.4 litres in 2016, and this trend is expected to continue until at least 2030[3].

Alcoholism causes around 3 million deaths annually, making it the seventh leading cause of death and loss of disability-adjusted life years[4],[5]. Deaths secondary to digestive diseases are the most numerous with 21%; hepatic cirrhosis stands out significantly among them[1].

Continued alcohol consumption causes histological changes in the liver including steatosis, inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, fibrosis and eventually cirrhosis. Clinically, the spectrum of alcohol-related liver diseases is very broad, ranging from steatohepatitis to advanced liver cirrhosis.

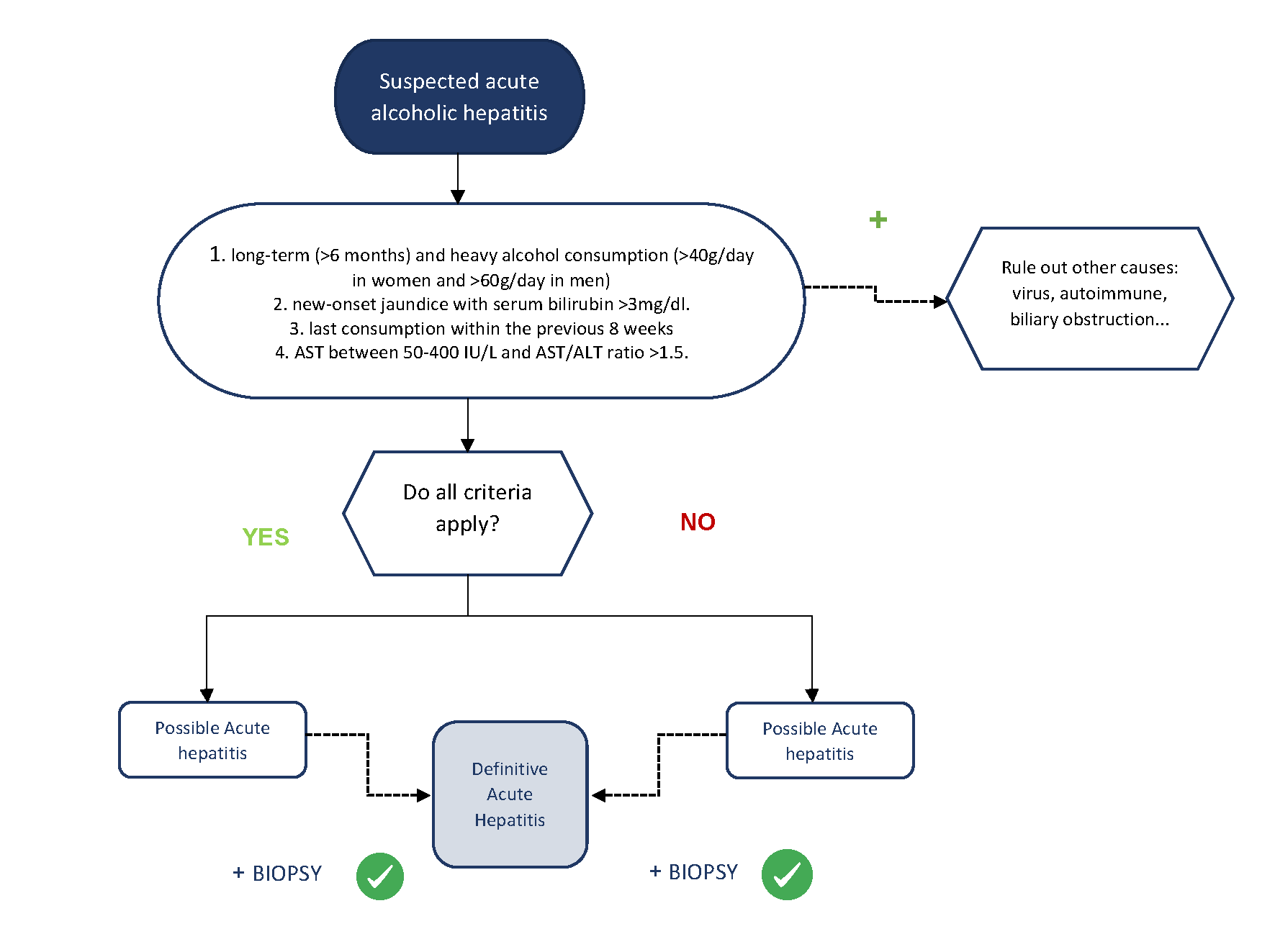

Acute alcoholic hepatitis (AAH) is a very particular entity within alcoholic liver disease. It usually occurs in patients with chronic alcoholism who present with an increase in alcohol consumption in the 4-6 weeks prior to onset. Patients develop a rapid onset of jaundice, associated with non-specific abdominal discomfort, asthenia and coagulopathy, with or without hepatic decompensation such as ascites or hepatic encephalopathy[6]. On examination, stigmata of alcoholism such as spider veins, bilateral parotid hypertrophy, exophthalmos or Dupuytren's disease, as well as painful hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly are common. In 2016, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) published a proposal to unify the diagnostic criteria for AAH[7]. This consensus estimated that the minimum amount of alcohol to develop AAH should be at least 40 g/day in women and 60 g/day in men, although these are often much higher. Patients often have a history of alcoholism of more than 5 years and it is common for patients to stop drinking alcohol a few days before admission, coinciding with the onset of symptoms. Alcohol consumption for more than 6 months and abstinence for less than 60 days are fundamental requirements for diagnosis. Analytically, patients should have serum bilirubin levels above 3mg/dl and mild-to-moderate elevation of transaminases, with an AST/ALT ratio >1.5. It is important to remember that AAH is the only acute hepatitis with transaminases below 10 times the upper limit of normal, so both AST and ALT must be below 400 IU/L. Finally, a diagnosis of exclusion must be made in which other pathologies such as viral hepatitis, Wilson's disease, biliary obstruction, Budd-Chiari syndrome or autoimmune hepatitis, among others, must be ruled out by performing the corresponding analytical tests and an abdominal ultrasound. In an epidemiological, clinical, analytical and ultrasound context as described above, the diagnosis of AAH can be established non-invasively. Liver biopsy would be relegated to the most doubtful cases, given the potential complications and restrictions in clinical practice (Figure 1). If required, a transjugular approach is usually necessary due to the presence of coagulopathy and/or ascites in most cases.

Several American and European studies state that the incidence of AAH shows an upward trend in recent years. In a retrospective Danish study, the authors reported an increase in incidence between 1990 and 2008 from 37 to 46 cases per million among men and from 24 to 34 cases per million among women[8],[9]. This effect has been exacerbated during the 2019 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19)[10]. Mortality varies according to clinical presentation, and can be as high as 70% per month in the most severe forms. Adequate stratification of patients is therefore essential to know the severity and prognosis in order to adopt an appropriate treatment plan.

There are a number of validated indices that are derived from analytical values and allow the identification of severe AAH on admission. The most commonly used are: Maddrey's Discriminant Function (mDF)(>32)[11], the MELD (≥21)[12], the ABIC score (>6.7)[13] and the Glasgow scale for alcoholic hepatitis (GAHS) (>9)[14] (Table 1). The Maddrey score or discriminant function (mDF) was the pioneer and is still used in clinical practice and clinical trials. However, a recent multicentre study of more than 2,500 patients evaluating the accuracy of different indices for predicting short-term mortality in AAH concluded that the MELD score may be more accurate than the mDF for predicting mortality in this clinical scenario[15]. The prognosis of these patients will depend directly on the severity of the episode and especially on the response to medical treatment.

Table 1

Variables of the most commonly used prognostic indices in acute alcoholic hepatitis.

This review aims to address the treatment of AAH from a practical and multidisciplinary point of view, including specific pharmacological treatment, management of malnutrition and deficiency states, prevention of withdrawal syndrome, and liver transplantation. With regard to the latter, the criteria currently in force in Spain for considering LT in patients with severe AAH are specified.

Pharmacological treatment

Complete abstinence is the mainstay for patients with AAH regardless of the severity of the condition. Continued alcohol consumption increases the risk of upper varicose gastrointestinal haemorrhage, ascites, encephalopathy and death[16]. In addition, it is important to carry out a global approach to these patients, paying special attention to nutritional management, vitamin deficiencies, as well as the treatment of possible decompensations (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy...).

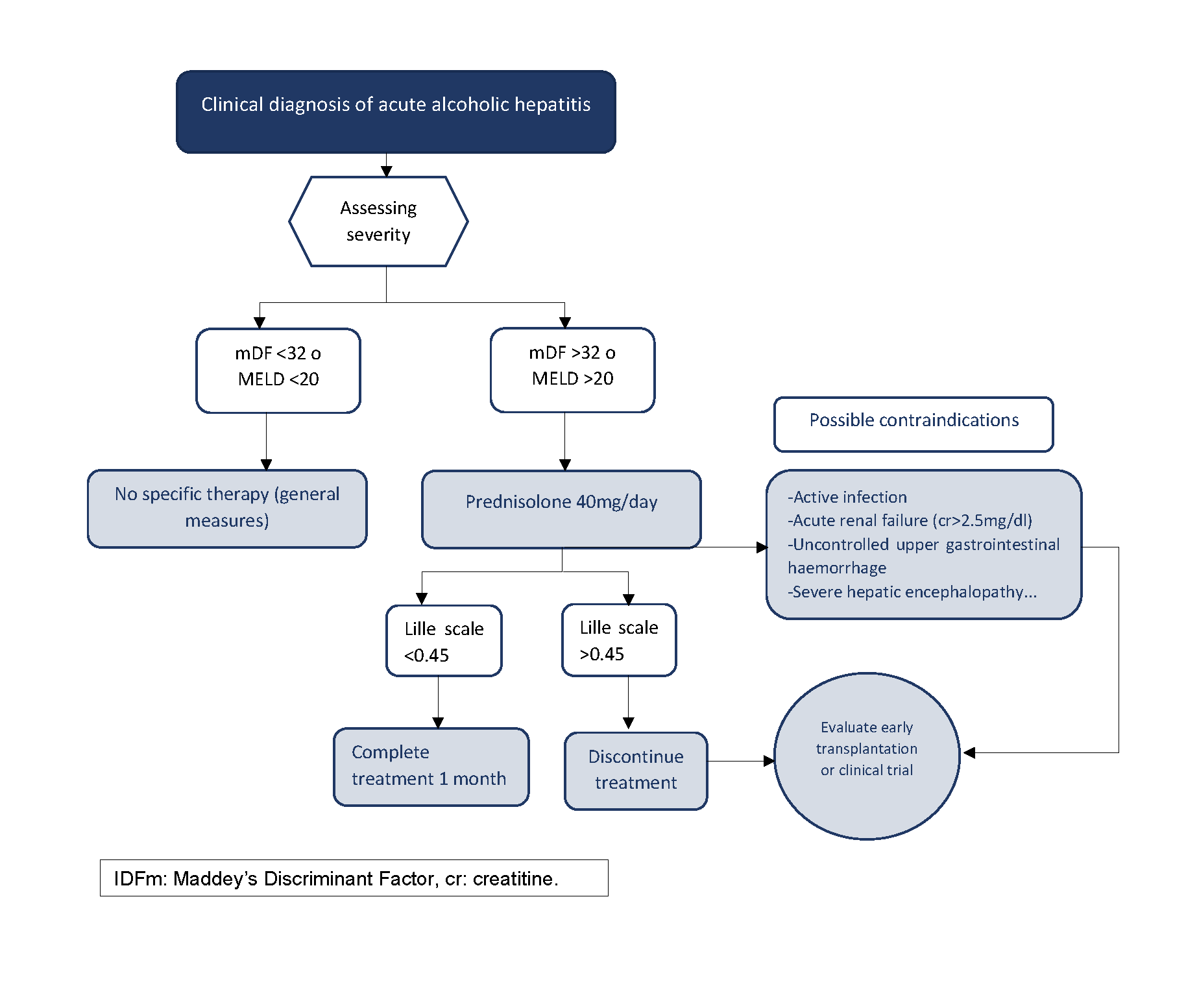

Prednisolone at a dose of 40 mg/day for 28 days is the first-line treatment recommended in all clinical practice guidelines for severe AAH. However, its use has been controversial due to inconsistent results in the studies that support it[17],[18]. To address this controversy, a multicentre clinical trial involving 1,103 patients was conducted in the UK between 2011 and 2014. This study concluded that corticosteroids improved survival at 28 days compared to pentoxifylline, but the benefit was not maintained at 6 and 12 months follow-up[19][19]. Given its limited benefit and potential side effects, the cohort of patients receiving this treatment should be appropriately selected. Patients must have severe AAH, defined by an (mFD) of >32[11]and a MELD of ≥21 although the benefit appears to be more pronounced in patients with a MELD between 25 and 39[20][20]. In addition, there are some relative contraindications that should be evaluated before starting therapy such as sepsis, severe acute renal failure, upper gastrointestinal bleeding....Once corticosteroids are started, it is important to identify non-responders in order to discontinue them early. The Lille scale is a dynamic scale based on the evolution of bilirubin levels in the first week (day 1 and 7) that predicts the risk of death. The Lille score dictates a standard of futility of corticosteroid treatment for those patients with a score above 0.45 on day +7, in whom treatment should therefore be discontinued[21][21](Figure 2).

Pentoxifylline (400mg every 8 hours orally) is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that has historically been used in the treatment of AAH due to the results of the Akrividiadis et al. clinical trial[22][22], which demonstrated a decrease in in-hospital mortality and the incidence of hepatorenal syndrome. Subsequent studies have failed to support these results. Two French trials failed to demonstrate the survival benefit of pentoxifylline, either in combination with corticosteroid therapy or as an alternative in patients not responding to corticosteroids[23],[24]. Similarly, the STOPAH study and several meta-analyses have failed to find any benefit with this drug [19],[25],[26]. Therefore, there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend the use of pentoxifylline in patients with severe AAH, although its use is still common.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has been proposed as a promising therapy given its antioxidant effect. It has been studied in multiple small studies both individually and in combination with other antioxidant agents, without being able to confirm an improvement in survival compared to standard treatment[27],[28]. The multicentre study published in 2011 by Nguyen-Khac, E et al[29] studied the effects of combined prednisolone and NAC therapy compared with prednisolone and placebo. Mortality at one month of treatment was found to be significantly lower in the corticosteroid arm with NAC, with a reduction in the rate of infections and hepatorenal syndrome. Thus, although the combination of NAC and prednisolone appears to be a promising treatment, its routine use in AAH requires higher quality evidence. It is administered intravenously with the following dosage: on day 1 at doses of 150, 50 and 100 mg/kg bw in 250, 500 and 1000 ml of 5% glucose saline at 30 min, 4 hours and 16 hours periods respectively and on days 2-5 at doses of 100 mg/kg bw in 1000 ml of 5% glucose saline per day.

In recent years, the number of clinical trials investigating new lines of treatment based on the pathophysiology of AAH has increased markedly[30]-[33]. Most therapies are aimed at promoting effective liver regeneration, controlling liver inflammation, reducing oxidative stress, or renewing intestinal dysbiosis.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) (5 μg/kg s.c. every 12h for 5 days) acts by mobilising haematopoietic stem cells and inducing liver regeneration. A prospective, randomised, double-blind study comparing standard therapy with and without G-CSF reported improved survival at 3 and 6 months, as well as a reduction in the rate of infections[34]. However, a recent European study failed to demonstrate this benefit[35]. Similarly, interleukin-22 (IL-22) in a current pilot study has shown a high rate of clinical improvement in patients with moderate-severe AAH with decreased markers of inflammation and increased markers of liver regeneration[36].

Although tumour necrosis factor (TNF) is an important mediator of inflammation, pilot trials with anti-TNF agents (infliximab and etanercept) were stopped prematurely due to increased sepsis mortality in the treatment arm[37]. Similarly, other anti-inflammatory molecules such as anakinra (anti-IL-1) have not shown greater benefit than corticosteroids in patients with severe AAH[38]. However, new clinical trials with other anti-inflammatory therapies, such as canakinumab[39] and DUR-928[40], are currently underway with promising results.

Metadoxine stands out among the antioxidant drugs under study. It has been shown to improve survival rates at 3 and 6 months in patients treated with prednisolone and metadoxine vs. those treated with the corticosteroid alone[41].

Alcohol-induced dysbiosis is associated with increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation, both critical factors for the development and progression of AAH. Therefore, therapies targeting the microbiota present another attractive line of research including faecal transplantation, the use of probiotics and non-absorbable oral antibiotics.

Nutritional management

Malnutrition consistently affects patients with advanced liver disease, with the highest prevalence rates and most severe forms identified in alcohol liver disease[42]. Such nutritional deficit is generated by liver dysfunction and the presence of a hypermetabolic state associated with decreased oral intake and intestinal absorption of nutrients. Specifically, in AAH the prevalence of malnutrition reaches almost 100% even in the earliest stages[43],[44]. These data are worrying as malnutrition is an independent risk factor for mortality and local/systemic infections[45]-[47].

Assessment of the nutritional status of the patient with AAH in the first days of admission is a fundamental aspect in order to provide individualised nutritional support. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) recommends the use of subjective global assessment (SGA) and anthropometric assessment to identify patients at risk, and bioimpedance to quantify the degree of malnutrition[48]. SGA is a simple tool that allows us to obtain information about the nutritional status of the patient through anamnesis (usual dietary intake, gastrointestinal symptoms...) and physical examination (presence of edema, ascites...)[49]. Due to the pathophysiology of liver disease, classical methods such as Body Mass Index (BMI), measurement of the tricipital fold or calculation of classical biochemical values (albumin, prealbumin...) are not suitable methods for assessing the nutritional status of these patients. Force measurement with a hand-held dynamometer, which is quick and simple, has been proposed as the optimal method. Moreover, it has been correlated with other markers of malnutrition in liver disease and is an indicator of functional status. Finally, bioimpedance is commonly used for the study of body composition and is recommended in patients with liver disease despite its possible limitations in hydropic decompensation.

Current clinical practice guidelines recommend an average protein intake of 1.2-1.5 g/kg per day and a caloric intake of 30-40 kcal/kg per day in patients with AAH[50],[51]. Surprisingly, an intensive enteral nutrition regimen via a nasogastric tube has been shown to be of no benefit compared to oral nutrition and may have serious side effects especially in patients with hepatic encephalopathy[52].

Apart from protein-calorie malnutrition, micronutrient (vitamin and mineral) deficiencies exist, although there is little evidence about the possible benefit of supplementation. Zinc deficiency is common in patients with ALD. Some studies[53],[54]have highlighted its role in maintaining the intestinal barrier and intracellular mechanisms that protect hepatocytes from alcohol-mediated injury. These potential benefits coupled with minimal side effects mean that supplementation is generally recommended in the treatment of AAH. Deficiencies of vitamin A, E, B12, D and magnesium are common, although there is insufficient evidence to support their supplementation in AAH[55].

Prevention of withdrawal syndrome

Approximately 50% of patients with heavy alcohol consumption develop some degree of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) after an abrupt cessation or reduction of alcohol intake[56]. The presentation of AWS varies from mild symptoms such as irritability, tachycardia, high blood pressure, hyperreflexia, anxiety, headache, nausea and tremors to severe forms with seizures, alcoholic hallucinosis, delirium tremens (characterised by mental status changes and intense autonomic hyperactivity), coma and cardiorespiratory arrest [57].

According to a recent systematic review, among patients hospitalised for any medical condition with a history of alcohol use disorder, 2-7% will develop severe AWS[58]. However, the incidence and clinical impact of AWS in patients with liver disease is unknown [59]. In the case of AAH, high alcohol intake and prolonged alcohol consumption, together with the need for hospitalisation, place the patient at high risk of developing AWS. A recent multicentre study evaluating the prevalence and clinical impact of AWS in patients with AAH concluded that AWS occurs in up to one third of patients admitted for AAH. In addition, patients who develop AWS were shown to be at increased risk of hepatic encephalopathy, infection and need for mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, in that study, AWS independently increased short- and long-term mortality in AAH and the use of high-dose intravenous sedatives to control AWS was also associated with worse outcomes [60].

Although clinical practice guidelines for the management of AAH include some comments on the management of AWS, there is little evidence to support that the routine use of prophylactic drug therapy is safe or effective. Thus, there is great variability in management[61]. Most European centres choose AWS prophylaxis in high-risk patients, including patients with AAH, whereas this practice is very uncommon in the United States[62].

Early identification of AWS is crucial for its correct management. Severity scales for AWS can be useful, although they are not validated in patients with AAH. An example is the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale (CIWA-Ar) where a score > 8 indicates moderate AWS and a score ≥ 15 indicates severe AWS (table 2)[63]. Symptom-based pharmacological treatment is recommended for moderate and severe AAS rather than fixed doses, with the aim of preventing drug accumulation [64].

Table 2

CIWA-Ar scale. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

Benzodiazepines are considered the gold standard in the treatment of AWS because of their efficacy in reducing withdrawal symptoms, the risk of seizures and delirium tremens[65]. Long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g. diazepam) provide greater protection against seizures and delirium, but short- and intermediate-acting benzodiazepines (e.g. lorazepam, oxazepam) are safer in elderly patients and in hepatic failure[66]. In Europe, the use of clomethiazole, a thiamine derivative with hypnotic and sedative capabilities, is widespread. Both benzodiazepines and clomethiazole have a potential risk of abuse, which is higher in patients with alcohol use disorder. Therefore, the use of these drugs should be avoided beyond 10-14 days and benzodiazepines with an intermediate half-life such as lorazepam should be chosen whenever possible. Other medications such as baclofen and sodium oxybate have been approved for the treatment of AWS, with the additional value that they are also indicated for the prevention of alcohol relapse [67]. The safety of current therapies has not been validated in patients with acute or severe hepatic failure, such as in AAH[68].

Liver transplantation

Classically, a minimum of 6 months of complete alcohol abstinence has been imposed before LT can be considered as an option. This fact, together with the lack of knowledge about prognosis, management problems on the waiting list and the negative social impact they sometimes represent, has excluded patients with severe AAH from being potential transplant candidates until a few years ago. However, the "6-month abstinence" rule has not been shown to predict the risk of alcohol relapse after liver transplantation[69]. In 2011, the Franco-Belgian group published the observational case-control study including an early liver transplantation protocol for patients with a first episode of severe AAH unresponsive to corticosteroid treatment[70]. Patients were considered as candidates for transplantation if they met the following criteria: strong family support, absence of psychiatric comorbidity and commitment of the patient and family members to indefinite complete alcohol abstinence. Under these assumptions, the percentage of transplants for severe AAH compared to the total number of transplants performed in the same period was 2.9%. A highly significant benefit in terms of 6-month survival was observed in the LT group compared to controls (77% vs 23%; p<0.001). There were 3 cases (11.5%) of alcohol relapse in the longer term but no patients developed graft failure and the authors concluded that the impact of alcohol relapse is limited. After this initial experience, several retrospective observational studies have followed which have reproduced the initial results of the Franco-Belgian group[71]-[74]. The post-transplant alcohol relapse rate in these studies ranges from 15% to 20%, which is also associated with an increased risk of cancer and graft loss. In the largest study to date, a North American multicentre study including 147 patients with AAH who underwent early liver transplantation, the rate of alcohol relapse was 17% and one patient died of acute alcohol intoxication[73]. Therefore, although LT offers a very pronounced survival benefit for patients with AAH who do not respond to corticosteroids, even greater than in other accepted transplant indications, alcohol relapse is a prevalent and clinically relevant problem that requires the application of very strict candidate selection measures, while adapting the post-transplant follow-up strategy.

In this context, the Spanish Society of Liver Transplantation (SETH) proposed to expand the criteria for liver transplantation in 2020, after years of progressive shortening of transplant waiting lists due to the generalisation of hepatitis C treatments and the increase in the donor pool in relation to asystole donation. Among the possible areas of expansion of transplant criteria, it was decided to incorporate AAH as a formal indication for liver transplantation[75]. Table 3 summarises the requirements for LT to be considered in a patient with AAH. For a patient with severe AAH to be considered as a potential transplant candidate, it must be a first episode of AAH in which the patient was unaware of previous cirrhosis. If the patient was aware of a previous diagnosis of cirrhosis or if the patient has had an AAH episode in the past and has nevertheless not been able to maintain stable alcohol abstinence, the patient should not be considered as a suitable transplant candidate due to the high risk of alcohol relapse. The second requirement is that it is a severe AAH, defined as mFD score > 32 or MELD ≥ 21, and unresponsive to corticosteroids (Lille model score ≥ 0.45 on day +7). In addition, a transplant evaluation should be performed in which no contraindications for transplantation are demonstrated.

Table 3

Requirements necessary to consider the option of liver transplant in patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis in Spain. The recommendations presented have been adapted from the consensus document on criteria for extending the indications for transplantation by the Spanish Society of Liver Transplantation (SETH).

In this scenario, multidisciplinary assessment is particularly important, in which a psychosocial assessment is essential to predict the risk of alcohol relapse, which is the main limitation for the inclusion of these patients in transplant programmes. Likewise, in the pre-transplant evaluation of these patients, special attention should be paid to the exclusion of latent infections and malignancy. A rapid discontinuation of corticosteroids would be prudent in case of non-responders according to the Lille index who are potential candidates for liver transplantation, since in the ACCELERATE-AH study, corticosteroids prior to liver transplantation were associated with increased mortality in the immediate post-transplant period, mainly due to infectious causes[73].

A key issue in these patients is to ensure lasting abstinence after transplantation, which is influenced by factors such as awareness of illness, existence of psychiatric comorbidities or other addictions, number of drinks per day, existence of repeated quit attempts and socio-familial support[76]. An association has been identified in different cohorts of younger age as a possible predictor of post-transplant alcohol use. A thorough and comprehensive assessment of all these factors by a multidisciplinary team including addiction specialists and psychiatrists is important[77]. The applicability of transplantation should be established on the basis of the degree of alcohol dependence, as well as the existence of factors favourable for lasting abstinence[78].

There are different standardised prognostic instruments that combine some of these parameters into a risk scale, but they are not designed for patients with AAH undergoing early LT and none of them has a solid external validation[79]-[81]. The SALT ("Sustained Alcohol use post-LT") score is so far the only one designed for patients with AAH and a pre-LT alcohol abstinence period of less than 6 months[82]. It assesses 4 parameters with a specific score for each of them and a final score ranging from 0 to 11 points (Table 4). It is a simple system with an acceptable ability to predict severe alcohol relapse post LT (AUROC 0.76). A SALT score <5 had a negative predictive value of 95% while a SALT score≥5 had a positive predictive value of 25%, which would be an unacceptable rate in the context of LT. In other words, following this system, the population prevalence of severe post-LT ethylism in the population would be 5%. Internal validation in the study indicated a good consistency of the model but it still lacks external validation[79]-[82].

Table 4

SALT scale. Prognostic instruments for predicting alcohol relapse after liver transplantation.

After liver transplantation, a multidisciplinary approach with the participation of different specialists such as hepatologists, addiction specialists or social workers is essential to adequately address the problem of alcohol relapse. This approach makes it possible to prevent relapse, to better interpret the different relapse behaviours and their appropriate treatment[83].

On the other hand, the patient transplanted for ALD has a higher cardiovascular risk than other aetiologies and is especially prone to develop head and neck and lung cancer. Therefore, especially modifiable risk factors such as tobacco use, obesity and sedentary lifestyle should be avoided[83].

Conclusions

Alcohol-related liver disease is a public health problem that is most severe in AAH. The incidence of AAH has increased in recent years, especially during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. In patients with severe AAH, prednisolone is recommended unless there is an active infection or active gastrointestinal bleeding. There is no evidence that other treatments such as pentoxifylline or N-acetyl cysteine increase survival in these patients. Prevention of withdrawal syndrome and individualised nutritional management are fundamental pillars in the treatment of AAH. In very selected cases with a first episode of AAH that does not respond to corticosteroid treatment, early liver transplantation offers a clear survival benefit, but the risk of ethyl alcohol relapse is significant, so a multidisciplinary approach is required, including joint assessment and follow-up with the addiction specialist.

Descargar número completo

Descargar número completo Download full issue

Download full issue